Ampersand Gazette #62

Welcome to the Ampersand Gazette, a metaphysical take on some of the news of the day. If you know others like us, who want to create a world that includes and works for everyone, please feel free to share this newsletter. The sign-up is here. And now, on with the latest …

&&&&

You’ve Been Wronged. That Doesn’t Make You Right.

We are living in a golden age of aggrievement.

If you’re on the left, you have been oppressed, denied, marginalized, silenced, erased, pained, underrepresented, underresourced, traumatized, harmed and hurt. If you’re on the right, you’ve been ignored, overlooked, demeaned, underestimated, shouted down, maligned, caricatured and despised; in Trumpspeak: wronged and betrayed.

Against this backdrop, reading Frank Bruni’s new book, “The Age of Grievance,” is one sad nod and head shake after another. Tending to our respective fiefs, Bruni writes, is “to privilege the private over the public, to gaze inward rather than outward, and that’s not a great facilitator of common cause, common ground, compromise.”

Individuals as well as tribes, ethnic groups and nations are divvied up into simplistic binaries: colonizer vs. colonized, oppressor vs. oppressed, privileged and not. People can determine, perform and weaponize their grievance.

The compulsion to find offense everywhere leaves us endlessly stewing.

But as Ricky Gervais says, “Just because you’re offended, doesn’t mean you’re right.” Being oppressed doesn’t necessarily make you good, any more than “might is right.” Having been victimized doesn’t give you a pass.

But it wrongs us all. And if we continue to mistake grievance for righteousness, we only set ourselves up for more of the same.

from an Opinion Essay by Pamela Paul in The New York Times

“You’ve Been Wronged. That Doesn’t Make You Right.”

April 25, 2024

Lately, it seems like everybody is feeling wronged about something. Just this morning, there was an article in The New York Times about a northern English municipality whose council decided to eliminate apostrophes from all street names and their signs. The entire county is in an uproar over it.

In fact, I’ve noticed a passel of reporting on betrayal. Every one of us shares the betrayal experience on one level or another.

There are three kinds of betrayal that correspond to three levels of forgiveness.

A word from our sponsor about forgiveness. First, it’s a good idea—especially in the face of betrayal. It is. Second, forgiveness is one of the most selfish acts in the world. Third, it is an act of will, not a feeling.

Lastly, I believe forgiveness is over-rated, over-practiced, over-recommended, and above all, urged upon those suffering way too early in the process of dealing with betrayal.

As I said, I think forgiveness is a good idea. But to use it before dealing with the feelings around whatever betrayed you is foolish, and ultimately, damaging. Feel the feelings. Let them come up. Sit with them. Allow them full sway.

Use your spiritual practices on them, and check in with your body. What’s really needed to forgive is simply willingness to forgive. You don’t even have to know how to forgive. Just be willing. And if you’re not yet, don’t. Try … willing to be willing.

The reason forgiveness is selfish, and necessarily so, is that whoever or whatever betrayed you is probably not spending a second thought on you or your hurt. Forgiveness takes care of you, and your feelings, not the other person. That’s called Amends.

Don’t do it too early, or too energetically. You can’t force forgiveness. Or, you can, but it will be to your detriment. There’s no point in growing scar tissue over infection.

Oh, and you don’t have to be willing to forget. That’s just alliteration run wild.

So here’s the process. First, and the easiest part, is to forgive the betrayer/s. That’s about them. Let them go. Second, forgive yourself for your part in it. There’s no need for forgiveness unless you self-betrayed in some way. Third, forgive Divinity for letting it happen.

Then, when the bad feelings arise again, and they often do, you merely forgive them again and again until you’ve let it go.

I liked the observation Frank Bruni makes about looking inward not always being conducive to resolving whatever has wronged you. It definitely “privilege[s] the private over the public, … and that’s not a great facilitator of common cause, common ground, compromise.”

I’d amend it slightly for effective dealing with betrayal. Yes, look within, find out what you’re left with in its aftermath. Feel the feelings, and then walk into forgiveness with eyes wide open.

It’s good for whoever ailed you. It’s good for you. It’s good for the planet.

&

Art Isn’t Supposed to Make You Comfortable

Instead, explore a more unsettling element: the humanity of the perpetrators. When I say “humanity” I mean their confusion, self-justifications and willingness to lie to themselves. Atrocity doesn’t just come out of evil, it emerges from self-interest, timidity, apathy and the desire for status.

Here was the distillation of a peculiar American illness: we have a profound and dangerous inclination to confuse art with moral instruction, and vice versa.

I’ve always found the sheer uncompromising force of American morality to be mesmerizing and terrifying. Despite our plurality of influences and beliefs, our national character seems inescapably informed by an Old Testament relationship to the notions of good and evil. This powerful construct infuses everything from our advertising campaigns to our political ones— and has now filtered into, and shifted, the function of our artistic works.

Maybe we would like to combat our feelings of powerlessness by insisting on moral simplicity in the stories we tell and receive. We’re so intoxicated by openly naming these ills that we have begun operating under the misconception that to acknowledge each other’s complexity, in our communities as well as in our art, is to condone each other’s cruelties.

While I typically share the progressive political views of my students, I’m troubled by their concern for righteousness over complexity. They do not want to be seen representing any values they do not personally hold.

But what art offers us is crucial precisely because it is not a bland backdrop or a platform for simple directives. Our books, plays, films and TV shows can do the most for us when they don’t serve as moral instruction manuals but allow us to glimpse our own hidden capacities, the slippery social contracts inside which we function, and the contradictions we all contain.

We need more narratives that tell us the truth about how complex our world is. We need stories that help us name and accept paradoxes, not ones that erase or ignore them. We have the audiences that we cultivate, and the more we cultivate audiences who believe that the job of art is to instruct instead of investigate, to judge instead of question, to seek easy clarity instead of holding multiple uncertainties, the more we will find ourselves inside a culture defined by rigidity, knee-jerk judgments and incuriosity. In our hair-trigger world of condemnation, division and isolation, art—not moralizing—has never been more crucial.

from an Opinion Essay by Jen Silverman in The New York Times

“Art Isn’t Supposed to Make Us Comfortable”

April 28, 2024

And good art most often doesn’t make us comfortable. It’s meant to be a challenge, and a challenge it is. But not, as Ms. Silverman says, the challenge of cancellation.

Oh, no. It’s the challenge of nuance. Furthermore, it’s the challenge of application—mostly especially to the self.

It’s all well and good to look at Guernica, Pablo Picasso’s masterpiece about war, but looking isn’t the same as seeing, and seeing isn’t the same as taking in, and taking in isn’t anywhere near the same as applying it to oneself to see where war and its atrocities live in us.

Binaries, we’ve all heard in the gender mishmash of our dominant culture, are necessary. From the midst of that very wise gender mishmash, we’ve heard, “Binaries are so limiting.”

Actually, they’re both. You can’t have a spectrum of anything without a binary, not even something as innocuous as a rainbow. Red starts the rainbow and violet ends it. We need some binaries for the purposes of starting and ending.

But we don’t need moral binaries. In fact, I’d go further and say we never need them, not even in a binary as drastic as Good and Evil because there is nothing that is ever absolutely one thing. There is always nuance between bifurcated extremes. Always.

Due to the love affair we’ve had with zeroes and ones, we’ve come to love the effortlessness of thoughtlessness. Oh, that’s good. Oh, that’s bad. Next. It’s facile, and ugly, and lazy, to boot.

Nuance is the name of the game in moral choice. Without it, we may as well all be Artoo-Detoo as human. Nuance is what Mr. Data strives so hard to learn on The U.S.S. Enterprise-D. Nuance is what gives flavor to life, and to art.

The word nuance comes from late eighteenth century French and sources in Latin that means subtlety. Binaries, Belovèd, are incapable of subtlety.

If, as so many of us claim, we want a new world, a better world, a healthy climate, a thriving culture, it’s time we walked away from binaries and made a dedicated commitment to nuance and the delicious, ongoing, challenging opportunity to hold the multiple uncertainties which we need to grow, heal, integrate, and thrive.

&

Here’s a universal affirmation. It works every time, for everyone, always and forever …

Danielle LaPorte

&

And in publishing news …

I’m still working with the local beta reader on those few scenes to make sure they’re perfect. It’s taking her longer than I thought it would to read and correct twelve pages, so the Gemma Eclipsing publication date is still pending. I’ve decided to let go and let it happen when it does. Me pushing the river only slows things down really. If you’ll think that over, you’ll find it tends to be true in everything.

Once again, if you haven’t seen it, here is the blurb for Gemma Eclipsing—Book Three of The Subversive Lovelies!

A rescue. An artistic vision. And her new vicety demands its immediate birth.

Gemma Bailey is the third of the Bailey siblings, yes, those Baileys. Known for being exceptionally talented on the stage, whether theatrical or domestic in nature, Gemma is given muchly to dramatics in the best sense of the word. She can make an occasion out of anything. She loves ritual. She loves pomp. She loves circumstance. She’s good at all of it, and she’s perfectly content with her legion of myriad friendships, no romance necessary.

Now it’s time for Gemma’s vicety—the third of four the sibs had planned upon the death of their beloved father seven years earlier. Since then, Jezebel’s pair of viceties—The Obstreperous Trumpet, a saloon, and The Salacious Sundae, an ice cream parlor—are going great guns. Jasmine’s vicety, The Board Room, the first of its kind in the City, is racking up the profits, all of which go to charitable causes. Gemma has been naming and claiming a music hall as her chosen vicety for years until the time arrives to make it happen.

Then, the extremis of a young painter causes a vision for a fine arts academy strictly for women artists to be birthed full-blown from Gemma’s eternally capacious imagination. And despite her abundant performance giftedness, Gemma discovers a fulfilling talent she never dreamed she had.

Will her vision engender the support it needs from all corners of the exclusively masculine art world? Will she struggle pointlessly to put forth her case? Or will an encounter with an unlikely colorful glass artisan change the whole game completely for Gemma and her vision for a vibrantly creative future for Chelsea Towers?

So, if you want the paperbacks, look carefully. There are two volumes for each title. If you want the Kindle, there’s one file for each title.

The first two of the tetralogy, Jezebel Rising and Jasmine Increscent can be found at these live links for ebooks and paperbacks.

And, in much-more-exciting-to-me news … I’ve started writing Jacqueline Retrograde, the first half of the eldest Bailey sibling’s story. Finally. I finished writing Gemma in October last year, and since then I’ve been researching and biding my time until I got that inner click that says Go! If I do it any earlier, I have to trash everything I’ve written and start again so after forty books, I’ve finally learned to wait for the signal. Writing Jaq’s backstory, and the Bailey sisters as children is a lot of fun.

&

I’m almost through Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show, which is a truly brilliant treatment of the extraordinary grass-roots activism accomplished by ACT UP/New York. I am struck over and over again by the united purpose which, despite human egos and infighting and the whole bunch of other shenanigans that we get up to, helped a hugely disparate group of people draw worldwide attention to a crime of gross neglect, wayward pride, and unexamined prejudice that was bigger, deeper, wider, crueler than I can even imagine.

Thousands of people were dying. Thousands, and governments, scientists, and the media stuck their fingers in their ears and sang out la-la-la-la-las like three-year-olds who didn’t want to hear that it was bedtime. The core of their behavior was the utter devaluing of just who those dying people were.

There is a deep and, please God, abiding spiritual lesson in how the gay community in particular handled those first few years of the epidemic. Part of what I get to do in this new series is to articulate it—out loud and proud.

I can happily, if somewhat startledly, (Is that a word?) report that since late April, one scene at a time of the new series is appearing on the page. At this point, I’ve written over twenty scenes. They startle me because I’ve never written in this way before. Most usually, I start at the beginning, go on till I reach the end, and then stop, to borrow from the Red King in Alice.

I do, however, know of an extremely successful writer who writes in scenes like I’m doing now, except she uses an outline. After she’s got them all written, she pieces together her novel. The author I refer to here is Diana Gabaldon, so clearly whatever she’s doing works. At the moment, I’m just showing up at the page, and doing what comes to me. Who knows what’ll happen to these scenes? Not I.

&

So many people dream about writing a book. An author friend of mine just this week told me that he had to finish his first book because the second one was already banging on his literary door. The thing is, though, you can dream all you want about writing a book, but the point is to start, and keep at it. If you know that you work best in accountability agreements, may I encourage you to reach out if you need book-husbanding, which includes coaching along the way? My husband, Tony Amato’s participation in my ongoing creative process makes his work invaluable to mine. If you need anything in your writing life, Tony Amato is the person. Find him here.

P. S. Whenever I say to him, as I wrote above, “Is that a word?” he always answers the same way, “It is now.”

&

This week I started reading several new things, almost all to do with book research for one series or another.

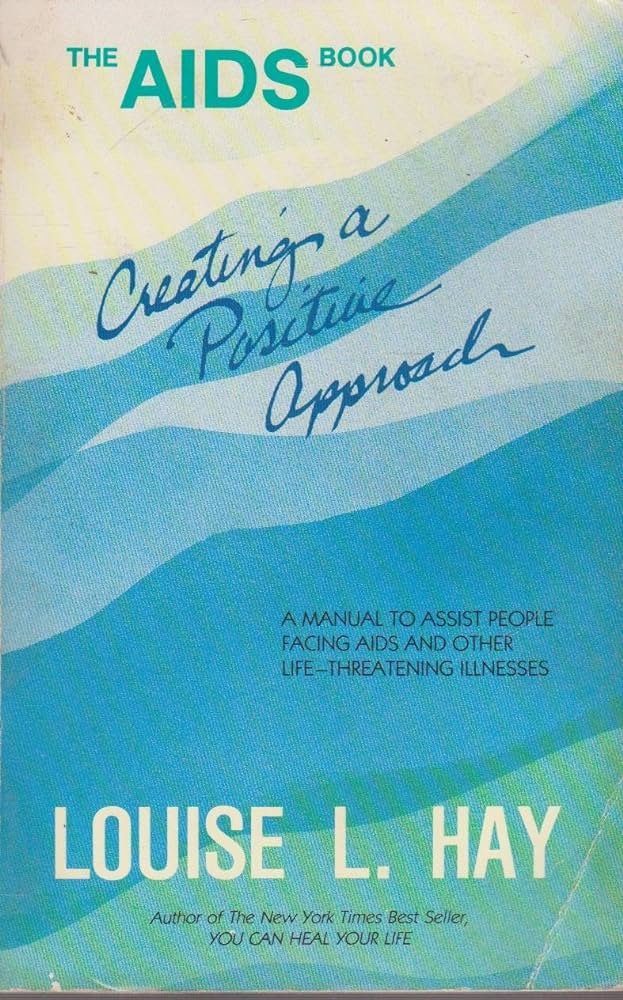

I found a copy of Louise Hays’ book AIDS: Creating A Positive Approach, and have begun reading a chapter a day. Louise Hay was one of the first spiritual teachers to open her heart and her arms to the community of gay men afflicted with, at that time, the death sentence that was HIV/AIDS.

Louise was a Religious Science minister who used a prayer model that the Holmes’ brothers named Treatment, or, now I think on it, maybe Mary Baker Eddy named it that. Anyway, the principle difference between the Fillmores’ Unity School and the Holmes’ Religious Science Institute was that the Fillmores talked about, taught about, and thought about heart, feelings, and emotions more than the Holmes brothers; their realm was Mind.

I also started reading Susan Brownmiller’s deconstruction of Femininity, written in 1984, a fascinating parsing of the things and ideas that culturally go toward signifying what a woman is. The first three chapter titles say a lot: Body, Hair, Clothes. The next one is Voice. Some of the ideas are wild lo, these forty years later. And, much to my chagrin, still true.

In addition, I reread Toby Tyler or Ten Weeks With A Circus, the 1881 prime example of a curious genre of literature written to teach children moral truths. Lots of these books were about running away to the circus. To no one’s surprise, when the boys ran away, they stayed and had adventures. When the girls ran away, if they ever got that far, they cried and hurried home so they were safe once again.

&

A photo shot one day when I’d gone to Davis Square

in Somerville, and noticed this

delicious stencil

on the sidewalk.

This week I’ve heard about a lot of tough

things happening to people, and I thought

we could all use a little reminder of

Who We Really Are.

I am, without doubt, certain that And is the secret to all we desire.

Let’s commit to practicing And ever more diligently, shall we?

Until next time,

Be Ampersand.

S.